PHOTO EXHIBITION

The visual narrative around disasters, especially those covered in media, largely revolve around the impacts of a disaster, the scale of destruction and immediate relief efforts. The visual medium in itself is quite often limited by its temporal nature and the context in which these images are consumed. In this larger picture of disasters that emerges, a visual narrative of what recovery looks like is often subdued. Using material from across the three states, this exhibition attempts to examine some ways in which recovery can be visually framed.

Yashodara Udupa & Zohrab Reys Gamat (2020). ‘Recovery with Dignity’ photo-exhibit during IIHS’ 5th City Scripts Festival.

As outsiders, we see that the communities affected by disasters right from the Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004 to Cyclone Gaja in 2018, have rebuilt their lives and moved ahead. But when we speak with residents, we realise the hidden, fragmented nature of this recovery.

In Kerala we found that interventions that go beyond the ‘one-size-fits all’ framework would be more effective in enabling recovery and building resilience within society.

The story of Markandi village is a unique example of how people have expressed their needs and made their voices heard which in turn had an impact on the nature of recovery that ensued. The exhibition includes aspects of their livelihood, housing and resettlement, daily life and touches upon their belief systems with regard to disasters.

TAMIL NADU

Fragmented recovery

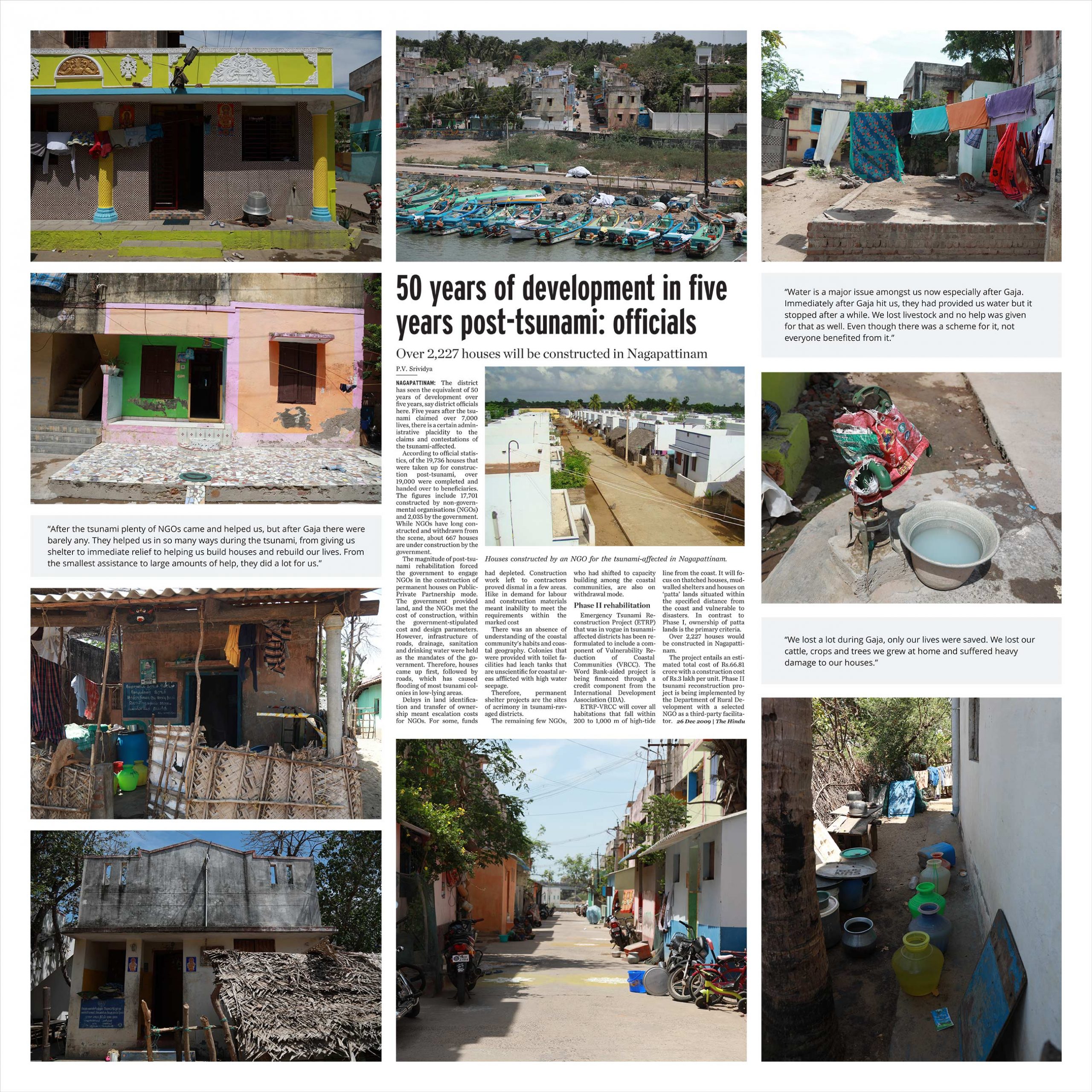

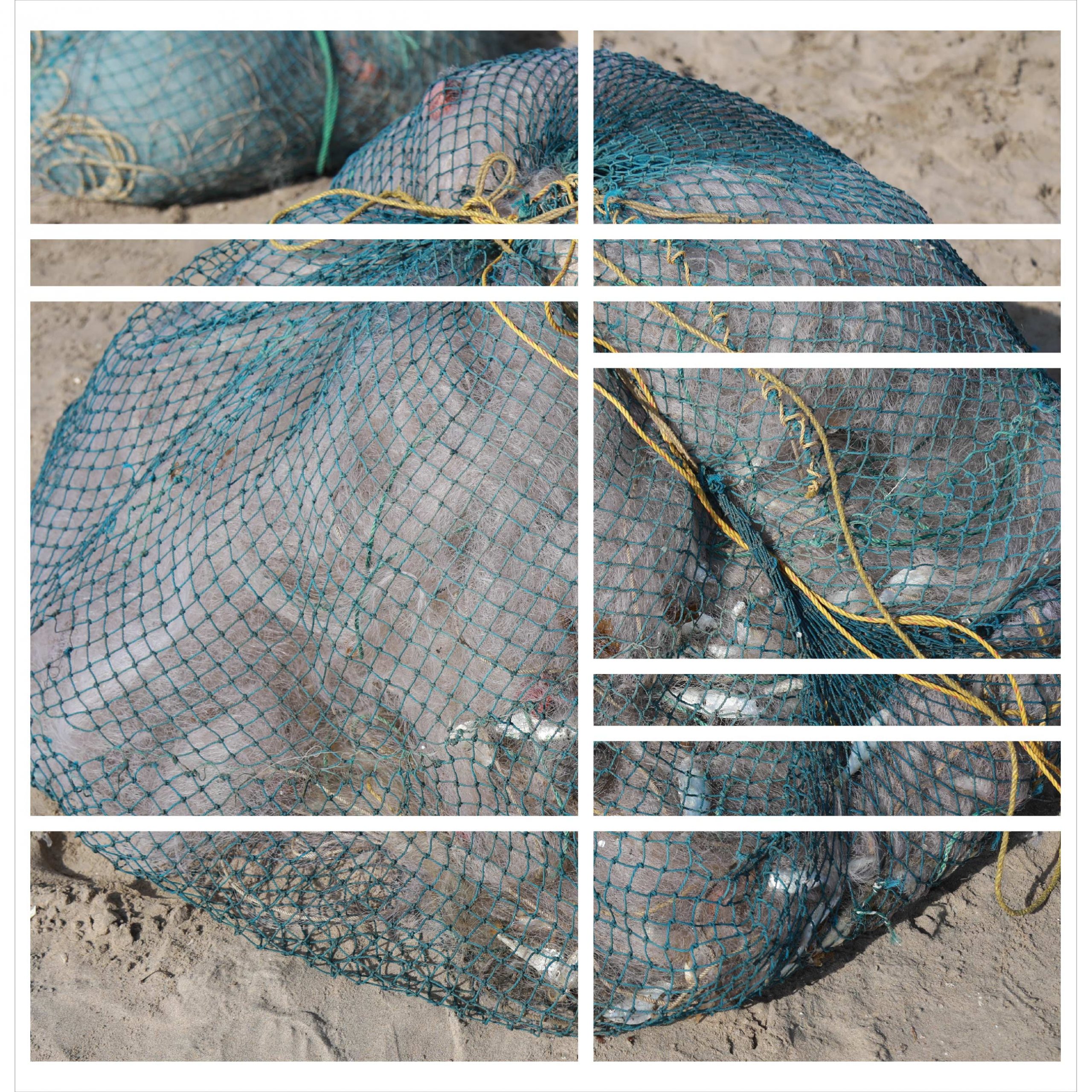

This exhibition presents a selection of images taken while on fieldwork in Chennai and Nagapattinam, along with excerpts from interviews and articles from newspapers, to understand the process of recovery from the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami and the 2018 Cyclone Gaja.

The exhibition hopes to, at least partially, depict the nature of post-disaster recovery in Chennai and Nagapattinam. As outsiders, we see that the disaster affected communities have rebuilt their lives and moved ahead. But when we speak with residents, we realise the hidden, fragmented nature of this recovery.

It is said that a disaster can be an opportunity to build back better. But the blurring of disaster recovery with development without examining forward and backward linkages or a holistic, systemic perspective could do less help and more harm. As one

respondent said, “It is impossible to forget such events and if things change for the better after them, then it is good. But if nothing changes then it just exists in our minds as a bad period in our lives, in the history of our people.”

| Curated by: Yashodara Udupa |

| With support from: |

| City Scripts Team | Colleagues on the Recovery with Dignity project from IIHS and UEA | IIHS Media Lab | IIHS Design team | IIHS Operations team | Social Need Education And Human Awareness (SNEHA), Nagapattinam |

| Articles from: The Hindu, The News Minute |

What does recovery look like?

All of us have seen pictures of several disasters – rising flood levels during excessive rains, falling buildings during an earthquake or the gusty winds during a cyclone. It’s harder to picture what recovery looks like. Away from the defining image that comes to

represent a disaster, this project explores what recovery looks like in Alappuzha and Wayanad in Kerala, post the floods in 2018.

The name Alappuzha comes from ‘Ᾱlayam’ meaning ‘home’ and ‘puzha’ meaning ‘river’. The extensive waterways are an integral part of the daily lives of the people with several everyday activities taking place on its banks. It is this topography that creates differential vulnerabilities and therefore plays a major role in determining recovery outcomes.

Marginalised communities often occupy low-lying, interior regions located in close proximity to rivers and paddy fields which are more prone to flooding. These areas lack road connectivity and this lack of accessibility increases transportation and overhead costs driving up costs of reconstruction. Households are forced to avail loans, adding to their existing debt burden, ultimately impacting their overall recovery process.

The name Wayanad comes from ‘Vayal Naadu’ meaning ‘the land of paddy fields’. Floods in Wayanad are common along river valleys in the rainy season in an average year. Landslides are less common but 2018 saw severe landslides that didn’t cause any deaths but damaged livelihoods and infrastructure. Of the 44 villages in Wayanad, 40 were affected by flooding or landslides that year.

Our research found that people in the landslide-affected regions take longer to recover since identification of new land that suits both the government and the people often takes more time than anticipated. Resettlement cannot merely involve the physical relocation of people and structures because livelihoods and lifestyles are often deeply connected with the land, space and the community. In these cases people often face new vulnerabilities such as the lack of economic opportunity and loss of community.

In both these places interventions that go beyond the ‘one-size-fits all’ framework would be more effective in creating the desired results.

| Curated by: Yashodara Udupa |

| With support from: |

| City Scripts Team | Colleagues on the Recovery with Dignity project from IIHS and UEA | IIHS Media Lab | IIHS Design team | IIHS Operations team |